Appearance

Understanding Insulin in Critical Care

Introduction

There are now so many different insulins out there that it's no wonder that for most of us not working in diabetes medicine, trying to remember what the difference between Toujeo and Levemir is beyond most peoples attention span when we have so many other important things to remember. There are many resources out there with cheatsheets to look up the duration of action of each of these insulins.

Rather than repeat that here, this will be an overview of what makes designer insulins different to insulin made in the pancreas and why it matters to our patients in ICU.

First it's important to ask the quesiton, why do we need them all in the first place, and why is this relevant to my practice in intesnive care?

Human insulin

For many decades after the isolation of insulin in dogs by Banting and Best, the mainstay of treatment for those with type 1 insulin was insulin isolated from the pancreases of cows (bovine) and pigs (porcine). This animal insulin caused loads of problems at the site of injection with skin reactions and immune reactions to the insulin itself. It wasn't until the discovery of recombinent DNA technology that human insulin could be produced by inserting human DNA into bacteria and mass producing insulin that has the same molecular structure to insulin that humans make in their own pancreas.

This insulin is what we commonly call "Human Insulin", you'll know it as soluble insulin Humilin S or Actrapid.

So Actrapid and Humilin S are exactly the same molecule as the insulin made in a healthy human pancreas. They act in the same way on cells in the body, increasing the uptake of glucose into muscle (and liver) and stopping the production of glucose by the liver.

So if it's the same molecule and it acts in the same way why do we need to change it? Surely it'll work just the same when we inject it?

Unfortunately not...

It's how we give it that matters

From the Pancreas

Insulin released from the beta cells in the tail of the pancreas enters the portal vein where it acts immediately on the liver to

- switch off glucose production (gluconeogenesis) - it's main effect on the liver

- move glucose transporters into the cell wall

- convert this glucose into glycogen (glyogenesis)

- switches off the production of glucagon by the alpha cells of the pancreas (they lie right next to the alpha cells)

Most of the insulin is taken up by the liver (70%) but the rest then circulates round to the muscles where it's main glucose uptake effect is

- it moves glucose transporters (Glut 4) into the cell wall and glucose is rapidly taken up by the cells for both energy (ATP) production and for storage (glycogen and fat)

This means that the onset of action is almost immediate and it can rapidly reduce glucose.

Importantly though the same is true of it's offset when blood glucose falls. The beta cells are very sensitive as glucose drops and stop insulin production. This results in glucagon production and a reversal of the above process, glygogen is turned into glucose and glucose is pumped out the cells of the liver into the blood.

This rapid correction to glucose falling only works if the beta cells can drop the circulating insulin to close to zero.

Into a Vein

When we administer insulin intravenously it still works quickly and has a powerful action but s it is given into a peripheral vein, the tight regulation at the level of the pancreas is lost. Most will be taken up by peripheral tissues and the amount getting to the liver is much less (normally 100% hits the liver first when made in the pancreas). This means it takes longer to kick in and we have to give a lot more, so the risk of overdoing it is much greater.

If blood glucose levels fall and we are fortunate to catch it with our monitoring,even after switching off the infusion there will be a significant amount of insulin circulating for a good while after.

Glucagon made in the pancreas in response to falling glucose levels cannot suppress the IV insulin already in the system, particularly if we are still giving it. The body's own safety mechanism will be over ridden and the insulin will continue to suppress the liver's ability to make new glucose in response to falling glucose.

Hypo's on IV insulin develop rapidly and can be life threatening. This is why monitoring must be so frequent.A patient on IV insulin must have their blood glucose checked every hour

Into the Skin

Whilst we use soluble insulin (humilin S and actrapid) intravenously on hsopital patients, all the other insulins out there are made for subcutaneous injection.

The problem with soluble insulin is that when injected under the skin the insulin molecules bind into hexamers (that's 6 molecules of insulin) each bound around a zinc molcule. These hexamers break down slowly (over a few hours) which means you get a peak after about an hour and they last for about 4 hours.

All the efforts from pharmaceutical companies over the years has been to make insulins that are either absorbed much faster (so that people with diabetes can match them up with their meals to avoid glucose spikes) or slow it right down (to provide a basal insulin that mimics what the pancreas does in health)

Boluses of actrapid or humilin S are far slower at controlling hyperglycaemia and much less predictable than IV insulin. In critical care it's probably much safer to use a VRII than correction doses

Short Acting Insulins

So, why don't we use on the fancy new rapid, short acting insulins as correction doses?

To answer this question, lets look at one of the fastest on the market as an example.

Fiasp is a relatively new "ultra-fast acting" designer insulin.

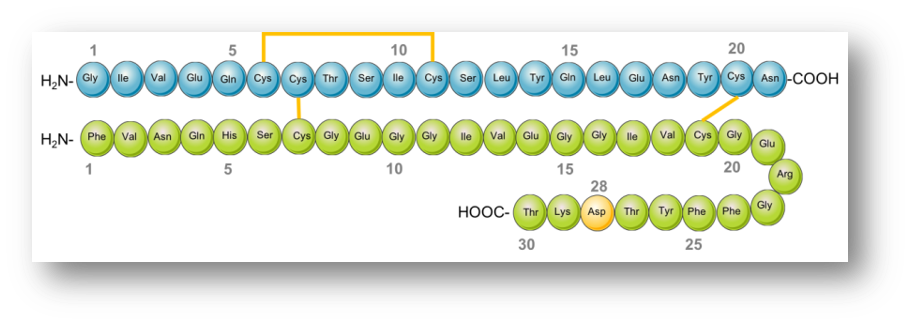

Insulin Aspart is the human insulin molecule with one amino acid (proline) replaced with aspartate - "aspart". Much like soluble human insulin this is then mixed with zinc. This is sold in the UK as Novorapid.

This small change in structure means the insulin hexamers are much less stable and they dissolve into the blood more quickly.

This process is sped up by mixing insulin aspart with nicotinamide (vitamin B3) which makes the hexamers even more unstable. The end result is FIASP, an ultra fast acting insulin that starts working within 10-15 minutes of injection.

This is fantastic for people who want a fast acting insulin to control glucose after eating. However all these pharmacokintetic models have been based on healthy volunteers.

Patiens who are critically ill can:

- be shocked with poor peripheral perfusion

- be on vasopressors which cause vasoconstriction

- have significant tissue oedema

- have marked acid-base disorders

- exist in inflammatory states with vasodilation ...all of which can have an unpredictable effect on absorbtion of subcutaneous medications like insulin. This means that the usual predictions of "take 1 unit for every 10grams of carbohydrate can be completely innacurate. For this reason we feel it is sensible to avoid using these medications in the acute phase of critical illness. They could be restarted later after the above risk factors have improved.

There are many aspects of critical illness that may affect the subcutaneous absorbtion of insulins and caution must be taken when prescribing short acting insulins for control of hyperglycaemia. It is likely safer to use a VRII until critical illness has resolved.